Mark Thompson

Author

I’m old enough to remember when aluminum foil was called tin foil—and well before it was folded into hats and worn by crazies seeking to stop the government from interfering with their brain waves.

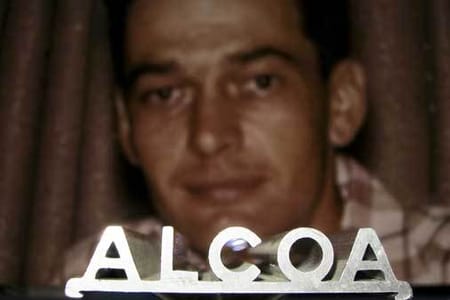

As a kid, aluminum was important to the Thompson household. That’s because my father’s trucking company shipped a lot of it. Such freight was memorialized in the super-cool extruded ALCOA logo that he brought home from work one day a half-century or so ago (it’s big enough to be a paperweight, but, being made of aluminum, not heavy enough). It has been a treasured memento in our living-room secretary for a long time.

Last fall I traveled to Pittsburgh, the one-time smelter of U.S. aluminum. Out one downtown hotel window you could see the iconic 1953 aluminum-clad skyscraper that served as the headquarters of the Aluminum Corporation of America—ALCOA—until 2001.

Out another window you could spy the lacy 1927 aluminum spire of the Smithfield United Church of Christ, the first use of the metal for a large-scale architectural piece.

The latest fight over aluminum brought the ALCOA ingot and other aluminumemories to mind. The approach of Father’s Day did the same for Dad, who’s been gone for a quarter-century.

There are certain “durables” in the national-security trade. Who pays for what, as President Trump’s recent tussles with NATO allies make clear, is one of them (otherwise known as “burden-sharing”). But just what that money pays for is another. And a big part of that is what defense experts call the “defense-industrial base” (which, like “national debt,” is a phrase designed to send readers fleeing).

As the tides of defense spending rise and fall in certain categories, contractors concentrate in some areas and abandon others. This can lead to fewer companies building things for the Pentagon (the number of airplane and shipbuilders has plummeted since World War II), as well as reduced supplies of the stuff needed to build those things.

That’s where aluminum comes in. There’s a glut of the stuff on the world market, some of it from China, which is depressing its price and could drive U.S. aluminum makers out of business. In April, the Trump administration launched an investigation to determine if the loss of U.S.-based aluminum—especially the high-purity variant used in U.S. armor and warplanes—poses a threat to national security. If it concludes that it does, it might restrict aluminum imports to assure its continued domestic production.

“As aluminum imports continue to rise, an investigation of the national security impact of those imports is warranted,” Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross said. “High-strength aluminum alloys have become among the most commonly used materials to make military aircraft and aluminum armor plate is used to protect against explosives and other threats.” Ross noted that imported aluminum jumped 18 percent from 2015 to 2016, and that “imports of semi-fabricated aluminum products from China grew 183 percent between 2012 through 2015.”

Aluminum has a checkered past in U.S. history. A 6-pound aluminum pyramid (at the time, the biggest piece of cast aluminum ever made), projected to cost the government $75, was placed atop the Washington Monument in 1884, signaling its completion. But, typically for a government contract, the final bill was $256.10 (the government ultimately paid $225).

Back then, aluminum was so prized that Napoleon III (the nephew of the “real” Napoleon) purportedly served the King of Siam with aluminum cutlery during his 1848-1852 tenure. Other guests at the dinner in his honor had to make do with gold.

Much lighter than steel, the Navy embraced aluminum following World War II so it could build bigger superstructures on its warships without making them top heavy. “Aluminum superstructures are generally 30 to 50 percent lighter than a comparable steel type and this allows additional weapons and sensors to be placed aboard for the same total topside weight,” a 1981 survey by the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers found. But, as always in military manufacture, there were tradeoffs: “…there are some penalties in the adoption of aluminum superstructure, namely, increased cost, reduced fire resistance, and less ballistic protection.”

Indeed, cracks in the metal—and concern about their fire safety after the USS Stark was attacked by Iraqi missiles in 1987, killing 37 sailors—led to a growing reliance on steel 30 years ago.

“The Stark's overheated aluminum superstructure kept reigniting fires for two days,” the New York Times editorialized. “The Navy pays close attention to fire control, and has recognized the faults of aluminum superstructures by reverting to steel in its latest hulls.”

The aluminum industry quickly returned fire. “Suggestions that marine aluminum can `burn’ simply are not true in the commonly accepted sense of contributing to combustion the way that wood or rubber does,” the Aluminum Association responded.

While aluminum has always been critical for aircraft, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq brought it added importance on the ground. The advent of improvised explosive devices—primitive (and sometimes not-so primitive) roadside bombs—proved to be a major killer of U.S. troops. The Pentagon spent nearly $50 billion on 24,000 Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected vehicles (MRAPs) for the wars.

“The application of aluminum armor plate for military vehicles has significantly increased during the past decade,” a 2011 SAE engineering study found. “Both U.S. Army and Marine Corps place great emphasis on lighter weight, higher agility and fuel efficiency as well as improved survivability.”

But increased aluminum imports have done what all such such episodes do: it led to the creation of the Congressional Aluminum Caucus in 2013.

The aluminum industry has pressed for trade restrictions on aluminum imports, and hailed Trump’s decision to launch an investigation into the matter (it will likely be months until a decision on what, if anything, to do, is reached). The Aluminum Association said the government should “address unfair trade practices that are hurting U.S. aluminum producers and fabricators.”

The U.S. aluminum industry is pressing for trade restrictions on aluminum imports, citing national security.

Aluminum makers in Hawesville, Ky., say their high-grade materiel saves American lives. “At the beginning of the Iraq War, the Humvees were folding up like pop cans,” one told the Washington Post May 29. “It was a really big deal until they started putting the different metals in.”

But, contrary to Ross’s claim of a flood of Chinese aluminum, more than half of of the aluminum imported into the U.S. last year didn’t come from China. It came from Canada, perhaps America’s closest ally and a nation that works closely with the U.S. on their mutual defense. Only 8.5% came from the Middle Kingdom, the Post noted in a June 1 editorial. “Canada is not pleased about being bracketed with China in this context—and we don’t blame our northern neighbor,” it added.

Beyond legitimate trade concerns is the military utility of armor. Just how much is enough? A reliance on beefed-up armor runs counter to what a lot of soldiers and Marines who have spent more than a decade fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq feel is a major problem. IEDs—and, more critically, the networks needed to produce and deploy them—suggest that at least a key slice of the local populace isn’t all that eager for U.S. protection. If that’s true, they say, the U.S. military shouldn’t be there.

Dad, of course, would understand all this. Jimmy Carter deregulated the trucking industry in 1980. That triggered widespread changes that drove him, and many men of his generation, out of the business.

He knew the world had changed. And he was smart enough not to fight the last war.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad.

Sent Saturdays