POGO Staff

Author

Too many officers and too few grunts and Pentagon civilian employees costs the taxpayers an extra $95 million a year, according to the General Accounting Office. In fact, the GAO has found that of 32,155 military officer jobs it studied, about 9,500 – or nearly 30% – could be replaced by civilian employees. Not only are taxpayer dollars being wasted, but too many officers in non-essential military positions is distracting the officer corps from its primary mission, thus decreasing the military’s effectiveness.

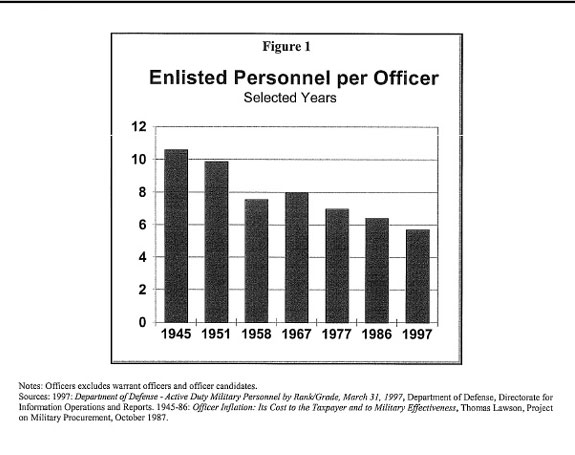

This report shows that our military has almost twice as many officers per enlisted personnel than at the end of World War II. In short, officer inflation in the U.S. military has reached an all-time high. At a time when pay for enlisted personnel is so low that some are on food stamps, money is being squandered on an excessively large officer corps.

The Project On Government Oversight's Executive Director, Danielle Brian, said, "Rather than safely reducing the relative size of our officer corps and getting more bang for the buck, we are spending more bucks for too much brass. The Pentagon uses officer inflation as one way to justify a bloated defense budget. We have more officers than we need--and we're running the risk of creating a military force of bureaucrats rather than warriors."

Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), commented on the report, “The POGO report clearly indicates that ongoing reductions in military personnel strengths are not being applied evenly across the entire rank structure. They are being applied at the bottom and not at the top. As a result, the military is now top-heavy with brass.” In 1945 there was one officer for every 11 enlisted personnel; now there is one officer for every six enlisted personnel. Some specific examples:

✪ ARMY. In 1945, the number of Army generals per active Army division was 14. In 1986, at the height of the Cold War, the army had 24 generals per division. Now, as we face no major threat, there are 30 generals per division.

✭ NAVY. At the end of WWII there were 130 Navy ships per admiral. In 1986, at the height of the Cold War, there were 2.2 ships per admiral. Now, as we face no major threat, there is an average of only 1.6 ships per admiral.

✭ MARINES. In 1945 there were 469,925 Marines commanded by 81 generals; by March 1997, 79 generals commanded a mere 173,011 Marines.

✫ AIR FORCE. In 1945 there were 244 aircraft per general in the Air Force. In 1986, at the height of the Cold War, there were 28 aircraft per general. Now, as we face no major threat, there are only 23 aircraft per general.

Generals and admirals have expanded into types of work that are, at best, loosely connected to fighting wars. Job descriptions for much of the officer corps include areas like: dentistry, academia, water works construction, and veterinarians. Specialty officers like those in public affairs and law along with others in areas like procurement and financial management have bloated the officer corps. Lower-ranking officers have served in jobs unrelated to combat such as working on congressional staffs--in potential violation of ethics rules.

Put simply, military officers cost more than civil servants. The GAO found in one case that converting military positions to civilian status would save $10,000 annually, per position.

November 10th, 1997, Defense Secretary William Cohen announced plans to cut 30,000 administrative jobs from the Defense Department. The initiative seems like a good first step--but--unfortunately, it focuses on eliminating civilian staff jobs, rather than tackling the bloated military officer corps. We are at a point where we can safely reduce officer numbers and restore a balance between officers and enlisted personnel. Some positions can be cut entirely, and others can be filled with less-expensive civilian workers.

POGO recommends reversing the trend of a rising relative share of officers, and particularly limiting the authorized ceiling on the number of generals and admirals. Administrative and support positions that do not need to be staffed by officers should be converted to less expensive civilian posts.

On November 10, 1997 Defense Secretary William Cohen announced plans to cut 30,000 administrative jobs from the Defense Department. The initiative would be laudable as a first step, but unfortunately it focuses on eliminating civilian staff jobs, rather than tackling the size of the military officer corps as well. Relatively few of the reductions in the proposal affect military officer positions, while those that do concentrate on reassigning the officers to other jobs, rather than eliminating the positions. Yet what sense does mere reassignment make when there are now close to twice as many officers per enlisted personnel as at the end of World War II?

Rather than reduce their ranks, the military services actually want the size of the officer corps to increase. The Defense Department has floated a plan to ask Congress for a sharp rise in the number of generals and admirals it is permitted by law to maintain.[1]

But as this report shows, the proportion of officers in the military is higher than ever before. Despite the end of the Cold War, increases in the relative size of the officer corps have not been halted - in fact they have continued.

The recent rare opportunity to bring the disproportionate share of officers down to a reasonable, post-Cold War level is becoming a victim of friendly fire - our own military and Congress are killing those chances, and defying common sense. Although the likelihood of massive war in Europe against the former Soviet Union has disappeared and the size of the military has been reduced, the number of officers in each service continues to rise well out of proportion to other personnel.

If history is any guide, we simply have more officers, generals, and admirals than we need, and we can safely reduce their numbers, restoring a balance between officers and enlisted personnel. Some positions can be cut entirely, as is called for by the reduction in the size of the force, and other positions can be filled with civilians, rather than with the more expensive officers.

A big part of this hoard of officers is hidden in a multitude of officers not intended for combat. Specialty officers like public affairs officers and uniformed lawyers along with others in areas like procurement and financial management have bloated the officer corps. A compelling need for such non-combat-related occupations to be filled by uniformed officers is questionable. The jobs do not necessarily require an officer and could be effectively performed by civilian employees or employees of private contractors.

If excess officers are not reduced, the nation runs the risk of creating a military force of bureaucrats rather than warriors. As General John Sheehan has said, if we’re not careful “we are going to be the best damned staff that ever got run off the hill.”[2]

In 1983, the Project on Military Procurement, now the Project On Government Oversight, issued a report revealing the excess size of the officer corps in the military.

This report discusses ways the excess number of officers cuts into military effectiveness while continuing to significantly bloat the still-enormous post-Cold War military budget.

For five years after the end of the Cold War, a congressional ceiling of 865 generals and admirals held. Despite the drawdown in total military personnel, in 1996 the Marines broke the dam, obtaining an increase in their number of generals. Although the Corps commissioned a study that found the Marines needed to expand their number of generals from 68 to 109, they “pragmatically” only requested an increase to 82.[3]

Despite a battle from Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), who noted that the Marine Corps “should not be topsizing when it’s downsizing,” Congress approved 12 extra generals.[4] In 1945 there was a total of 469,925 Marines[5] commanded by 81 generals.[6] Yet in March 1997, two fewer generals commanded a mere 173,011 Marines.[7]

A partial rationale for the increase in Marine generals was that colonels were doing generals’ jobs, and should have the appropriate rank. Curiously, then, the Marines kept the 12 colonel slots that were in theory translated into general slots, and instead deleted slots for 1 major, 5 captains, and 6 first lieutenants. Normally this phenomenon is known as “grade-creep,” but the Marine Corps’s trading of first lieutenants for generals should perhaps be better called “grade-leap.” The extra generals cost about $713,000 per year more than the lower officers.[8]

Naturally, the extra generals given to the Marines sparked the other services to “join in” and ask for more. In 1997 the Defense Department floated a plan to ask Congress to authorize 54 new generals and admirals in the active forces and 32 in the reserves. The plan met with some skepticism. A General Accounting Office (GAO) review of the report behind the numbers found that “DOD’s draft does not clearly identify requirements for general and flag officers [admirals] and does not explain the basis for its recommendations to increase the number of general and flag officers.”[9]

The number of additional generals and admirals that the Pentagon requested appears to be arbitrary: the military services wanted a total of 132 new active-duty generals and admirals, the civilian service secretaries wanted only 32 more, and the Defense Department settled on something in the middle. The GAO noted the subjectivity of the process: “The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Joint Staff selected different methodologies for the studies. The different methodologies together created at least 24 different definitions of a general or flag officer.”[10]

The military services have also been asking Congress for permission to boost the other officer ranks. For example, despite reductions in the size of the military and the threats it faces, in 1996:

In 1945, World War II was coming to a close. In the summer of that year, with fighting still underway, the huge U.S. military establishment was at the peak of its strength. Yet despite that effective force and its impressive victory, the military today claims it is necessary to keep about twice as many officers per enlisted personnel as at the end of World War II. Similarly, even though the military challenge facing the United States is far smaller than during the Cold War, officers make up a higher share of the force than at any time in the Cold War.

In 1945 there was one officer - ranging from lieutenants and ensigns through generals and admirals - for every 11 enlisted personnel. Now there is one for less than every six enlisted people. The following chart shows the trend in the ratio of officers to enlisted personnel.

What the Numbers Show

✰ Figure 1 shows that the trend of more and more officers relative to enlisted men and women has continued to worsen since 1945.

✰ We are now at the point where there is an officer for every six enlisted personnel.

✰ In June 1945 the military had 2,068 generals and admirals on its rolls. In March 1997 the services had 879 generals and admirals - for a total force only about one eighth the size of the 12 million-strong World War II force.

✰ In 1986, while the Cold War was still going on strong, we had more than six enlisted personnel per officer, whereas now we have fewer than six.

The trend of an increasing share of officers in the military pie is not a new phenomenon, although it is less justified than ever before since the United States faces a very small relative magnitude of potential threats now. Throughout the century, despite fluctuations inspired by the outbreak of war or peace, the officer corps has been able to secure a steadily-increasing share of the military pie for itself, leaving crumbs for enlisted personnel.

The following graph shows military officers as a percentage of total active duty military personnel.

What the Numbers Show

✰ The graph indicates that officers continue to account for an ever-larger share of military personnel.

✰ The figures show a general trend in recent U.S. wars: the percentage of officers has dropped at the opening of hostilities, with the influx of enlisted draftees, then it has risen during the course of wars. After peace arrives, however, the share of officers has not dropped back to pre-war levels and stayed there. Rather the percentage has steadily increased with a ratchet effect.

✰ The reduction in the share of officers in the military after the end of the Cold War has been far smaller than drops after World War Two and the Vietnam War.

✰ Despite the end of the Cold War, the share of officers continues to rise.

The following table (Figure 3) shows the current ratios of enlisted personnel to officers in the different services.

What the Numbers Show

✰ The Air Force has the highest percentage of officers, at 1 officer for every 4 enlisted personnel.

✰ Even the reputedly lean Marine Corps has an officer for every 9 enlisted people.

Naturally, as the military was reduced from 12 million personnel at the end of World War II to 1½ million in the active forces today, the absolute number of officers was also reduced, albeit not proportionately. Furthermore, different ranks of officers were reduced at widely disproportionate rates. The top officers - generals and admirals - took smaller percentage size reductions than junior officers such as lieutenants and Army captains. Colonels, lieutenant colonels, and Navy captains and commanders were reduced least of all.

The following table (Figure 4) shows percentage change in size of different ranks from 1945 to 1997. The table shows that junior officers have faced a disproportionate share of the overall reduction in the officer corps, with the upper ranks holding onto their jobs with more success than the lieutenants. This is another manifestation of “grade-creep.”

What the Numbers Show

✰ Colonels experienced the lowest relative reduction, dropping only a quarter from 1945 to 1997, while the enlisted personnel dropped 89%.

✰ The number of generals and admirals dropped only 57% from 1945 to 1997, while the number of 2nd lieutenants and ensigns dropped 90%.

The next few tables focus on the top brass: the generals and admirals. In each service the number of generals and admirals relative to other measures has increased, especially when compared to the end of World War II.

Curiously, the Congress recently took action that may increase pressures to keep an excess number of generals: the Fiscal Year 1998 Defense Authorization Act raised the limit on how long generals and admirals may stay in their posts, by three years in the case of three-star officers (lieutenant general and vice admiral), and by five years in the case of four-stars (full generals and admirals).[12] Allowing the top brass to remain in office longer reduces the number of openings available, potentially fanning interest in creating more positions. But as the following charts indicate, the problem is not so much a shortage of generals and admirals, as a surplus.

What the Numbers Show

✰ Since the 1980s, the number of Army generals per division is increasing again.

✰ There are now more than two times as many generals per division as there were at the end of World War II.

✰ In 1986, at a time of great Cold War tension, the number of generals per division was lower than now at just 24 per division rather than 30.

✰ An Army division is actually commanded by just three generals.[13] But the Army has a total of 30 generals on its overall staff for every active-duty Army division in the force.

What the Numbers Show

✰ Figure 6 shows that despite admirals in World War II proportionately handling 130 ships each, today admirals are responsible for only 1½ ships each. Put another way, it takes 81 admirals today to supervise, in effect, the number of ships supervised by one World War II admiral.

✰ In 1986, when we stood ready to fight World War III at a moment’s notice against the Soviet Union, there were more ships per admiral than now: 2.2 ships per admiral versus just 1.6 now.

✰ We are now at the point where there are two admirals for every 3 ships in the fleet.

What the Numbers Show

✰ Even though the Marine Corps has almost the same number of generals as it did fifty years ago, it is only about a third as big as it was then.

✰ During the Cold War, the Marines stood ready to fight the Soviet Union and other nations with a much higher ratio of Marines to generals than they have now.

✰ It will be much more difficult for the Marines to maintain their reputation as the “lean and mean” service if they continue the trend shown above.

The Air Force has a similar situation (see Figure 8).

What the Numbers Show

✰ Now there is more than one Air Force general for each squadron in the Air Force. A fighter squadron normally would have just 24 or fewer aircraft.

✰ In 1945, there were only 22 more generals in the Army Air Corps (the predecessor to the Air Force) than there are today, but they were responsible for 66,000 more aircraft than today’s Air Force generals.

✰ In 1986, at the height of the Cold War, there were more aircraft per general than now: 28 aircraft per general versus 23.

The various measures illustrated in the charts above all tell the same tale: in the case of each branch of military service, the relative number of top officers has increased sharply over historical levels.

Both a cause and effect of the increase in the relative size of the officer corps has been its expansion into work areas that are unrelated to combat and do not necessarily need to be performed by uniformed officers. Officers occupy slots in financial management, public relations, procurement, and law that are far from combat and weaken their skills in war leadership and command. Some officers are not even trained for combat unit command and never receive such commands.

A cursory look down the official roster of generals and admirals brings up a large number of positions that should raise more than eyebrows. No doubt the Defense Department has rationales for why each of these positions must be filled by an officer - but common sense suggests that the military would be stronger if its top ranks focused more on warfighting and less on administrative matters.

For many of these functions the importance of the activity is clear. What is not clear is why the activities must be performed by high-ranking, highly-paid, uniformed military officers. Plenty of civilian specialists could do jobs that do not require deployment with the troops to a combat zone.

The GAO found that various not-militarily-essential general and admiral positions could be converted to civilian positions:

For example, the Navy uses an admiral to command the Naval Exchange Service, while DOD uses a civilian to manage the Defense Commissary Agency. Also, the Army uses a brigadier general as its Director of the Center for Military History, while the other three services use civilians in similar positions. In addition, the Army, Navy, Air Force and Defense Finance and Accounting Service together use eight general and flag officers ranked as high as major general or rear admiral (upper half) in various financial management positions that are also candidates for conversion based on our criteria. Other general or flag officer positions in the services and the joint community may also be candidates for conversion.[14]

The list that follows shows that our top brass has become bureaucratized and tied up in staff work. Where has the breed of “warriors” gone? Generals and admirals listed below are spending their time on business management, legal processing, dentistry, public affairs, “liaison” with Congress, building water works, academia, criminal investigation, and other activities far from combat.

A vivid example of officer positions that may not be needed since they involve work with no clear relationship to combat is provided by the congressional military fellows programs. These programs detail officers to Members of Congress and congressional committee staffs. Apart from the lack of military need, the positions raise even deeper questions about violation of ethics rules.

Former Representative Patricia Schroeder was reportedly stonewalled merely getting the Defense Department to reveal how many “fellows” there were at one point. Estimates ranged from several dozen to over 100, including four for House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA).[15]

Some of the fellows’ duties reportedly included: creating an orientation manual for new Republican members of Congress; helping a task force restructure House committees; and bringing better management to Gingrich’s leadership office.[16] The potential for engaging in partisan activities such as this is high when officers are detailed to Congress. Furthermore, conflict of interest questions are raised, because officers are prohibited from “lobbying” Congress, yet the opportunities to do so while detailed to congressional staffs are numerous. Rep. Schroeder charged that the goal of this “congressional temp service” is “to keep members happy and grease the wheels for defense appropriations.”[17]

Rules governing the detailing of officers were tightened somewhat in 1997, but the Senate stalled a Pentagon Inspector General investigation of the activities of detailed officers. One senior Senate aide’s unfortunate attitude was: “It’s none of [the Inspector General’s] damn business what they’re doing as long as they’re not participating in partisan politics.”[18] Another Pentagon Inspector General report, finding that “Of the 49 congressional details we identified, 47 were not made in accordance with DoD policies and procedures for detailing personnel to Congress,”[19] called for improved management controls.

If the military can afford to use officers in dubious positions as congressional aides, it is one indication that there are more than enough officers in the officer corps.

The U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) recently studied the problem of military officers filling positions that could be carried out by civilians. The GAO found that putting Navy combat officers in bureaucratic positions has contributed to the Navy’s poor financial management. Navy line officers - understandably, given that their purpose is warfighting - were not well-suited for the job:

The Navy has staffed its military comptroller positions with individuals who, on average, lack the depth of financial management experience and the accounting education needed for the financial management environment of the 1990s. Line officers, who fill most of the senior-level comptroller positions at the captain and commander ranks, have spent almost their entire careers in command positions such as surface warfare officers, aviators, or submariners.[20]

This not only reduces combat readiness, but has a heavy financial cost. GAO found

... long-standing, serious financial management deficiencies in the Navy. We stated that the Navy’s financial reports were of little value in assessing its operations or the execution of its stewardship responsibilities. Our work identified substantial misstatements in almost all of the Navy’s major accounts and $225 billion in errors in the Navy’s fiscal year 1994 financial reports.[21]

GAO summed up its attribution of the financial problems in part to the Navy practice of putting combat officers in financial management positions by saying:

In the military combat operations environment one would not expect an officer with only 3 to 4 years experience to command a ship, squadron, or fleet. Similarly, one would not expect a comptrollership, responsible for billions of dollars, to be staffed temporarily by a less than fully experienced financial manager.[22]

Other services have fewer line officers in comptroller positions. The Army and the Air Force put officers in career tracks dedicated to financial management. This reduces the problem of warfighting officers unable to handle management, but since those financial officers are not meant to fight wars, raises the question of why the positions need to be staffed by military officers at all.

The General Accounting Office has suggested converting jobs that do not need to be filled by officers to civilian positions. Using the Defense Department’s own criteria, the GAO found that about 9,500 of the 32,155 positions it examined could be converted to civilian staff.

The Army, the Navy, and the Air Force are currently staffing officers in about 9,500 administrative and support positions that civilians may be able to fill at lower cost and with greater productivity due to the civilians’ much less frequent rotations. Examples of career fields that contain positions that might be converted are information and financial management.

DOD could save as much as $95 million annually by converting the roughly 9,500 positions we identified.[23]

The Defense Department wrote its own guidance on whether to fill slots with civilians or officers in 1954. Although the guidance required civilian use wherever possible, it gave the Defense Department a lot of leeway to use uniformed officers. It is clearly time to update and tighten the policy.

Giving jobs to military officers that can be performed by civilians and keeping more uniformed officers than are needed in the military entails a double cost to the government: money has to be found not only for the basic salaries of extra positions, but also for the extra benefits due to military personnel.

Military personnel fully deserve the extra benefits above basic pay they receive - for their service to the nation, the hardships they endure in performing their work, and their willingness to risk their lives. But it must be recognized that these benefits do cost the government more, and therefore creation or preservation of a high number of officer positions should be examined much more closely. Naturally, admirals and generals are particularly expensive, so particular attention should be paid to ensure that their positions are reserved for essential military work.

Additional costs to the government for benefits that are not always available to civilian employees or to private sector employees include:

❒ Education at government schools, or educational expenses at private schools

❒ Provision of free or subsidized housing

❒ Subsidized shopping at post exchanges and commissaries

❒ Provision of comprehensive health care services

❒ Various incentive and duty pay - for example, combat pay and flight pay

❒ Recreation facilities

❒ Tax exemption for certain types of compensation, and

❒ Retirement and veterans benefits.

The bill for military and civilian personnel in the Defense Department was $70.1 billion in 1997. The “Family Housing” account added another $4.4 billion.[24]

In an October 1996 report, the General Accounting Office calculated that each officer position converted to civilian staffing that they examined could save an average of $10,000 annually.[25] The following table (see Figure 10) from the GAO report provides comparisons of military and civilian personnel costs:

The Defense Department’s recent draft plan to increase the number of generals and admirals by 54 active-duty and 32 reserve positions would entail extra cost for the government. The GAO estimated the extra funding requirement to be at least $1.2 million annually.[26] The cost would be substantially more if the services did not reduce the number of colonels and Navy captains by the same amount as the increase in generals and admirals.

At a time when the services are facing a “brain drain” of skilled personnel, such as pilots, they cannot afford to waste funds on keeping excess officers on the payroll where they are not needed.

In addition to the financial cost, a second potential cost of maintaining a large number of officers is that it may actually reduce military effectiveness. An excessively large officer corps robs resources from other military needs. As more and more officer corps migrate into non-militarily-essential activities, the officer corps may become increasingly distracted from its central mission and lose its fighting edge.

One top officer has spoken out against the growth in military staffs and “commands,” arguing that the excess staffing is taking money from buying more weapons and funding other military priorities. In 1996, General John Sheehan, then commander of the U.S. Atlantic Command, pointed out that:

✰ the Army had only 125,000 personnel who are “warfighters,” compared to 375,000 uniformed support personnel and 300,000 civilians - “that works out to only 16% of the total force”

✰ there were 23 military commands in charge of 60,000 U.S. troops in Europe

✰ NATO had 65 headquarters with 21,000 staff officers doing paperwork

✰ in the Department of Defense “there are 199 separate staffs at the civilian and the two-star-and-above flag officer level”

✰ the 150,000 service members within 50 miles of Washington DC outnumbered the entire personnel in the warfighting Atlantic Command

✰ the infrastructure of the Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington cost $42 billion annually.[27]

Similarly, the General Accounting Office reports that at the end of fiscal year 1996, about 46 percent of active duty officers were in support positions such “as civil engineering officers, personnel officers, and veterinarians.”[28] General Sheehan challenged the services to re-examine their priorities in light of these officer-heavy staffs.

Recent wars fought by the United States show a pattern: the percentage of the total U.S. force taken up by officers has initially dropped as large numbers of enlistees are drafted into the ranks, but by the end of the war, the officers’ relative share of the force has risen. More importantly, after the war, the percentage of officers has not returned to the lower pre-war levels. The services tried to keep relatively more officers during peacetime demobilization, on the theory that already-trained officers would be needed to handle the expansion of the force and another influx of relatively unskilled draftees at the start of the next war.

But war has changed, as has the U.S. military’s way of fighting. Increasingly, the military is substituting technology for bodies. Its plans for future “come as you are” wars are not to greatly expand the force with draftees, but to use existing forces, and if necessary, to mobilize the reserves. So although the services might claim they need more officers in peacetime as a base for the next war, plans for likely future wars do not call for an active force expansion needing extra officers, and the reserves already have plenty of officers.

The Air Force has tried to justify its requests for more generals by citing:

✏ “the number of contingency operations”

✏ “the overall operations tempo”[29]

while the Army has mentioned:

✏ “the increased complexity of operations”

✏ “the consolidation of organizations” [surely this would reduce command positions?]

✏ “the duration and magnitude of joint and international operations”

✏ “the management of systems and programs”

✏ “increased joint and coalition requirements” and

✏ “statutory requirements” such as the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act.[30]

These responses may sound weighty, but their plausibility comes from ignoring how the current situation compares with other times. The current operations tempo hardly compares favorably with the pace of World War II, the current complexity of operations surely does not match campaigns such as the amphibious reconquest of the Pacific in that war, and the current number of peacekeeping operations is not nearly in the same league as fighting hordes of Soviet divisions in a global World War III. Yet now the relative number of officers and generals and admirals is higher by various measures than in those earlier periods.

The services have emphasized the need for more top brass to handle new “joint” service activities. But if the separate services are losing generals and admirals to joint positions, it makes sense that the services should be able to reduce their own staffs in accordance with their reduced functions. The idea should be to transfer functions to joint operations, not merely add new joint functions and keep all the old ones.

The purported need for more generals to “manage systems and programs” sounds like the problem identified in this report of officers expanding into non-military functions such as procurement management, administration, law, and so on.

If resources were no object, it would be fine to keep more than enough staff to do the job - all organizations strive to expand their labor resources if they can. But given the reduced military challenges and reduced force size compared to World War II and the Cold War, it appears that in the case of the officer corps, the phenomenon of “the work expanding to fill the labor available” is in operation.

The following recommendations can reverse these trends and help the officer corps keep up with some of the changes underway in the rest of the military following the end of the Cold War.

☞ Reverse the trend of increasing the relative size of the officers corps by lowering the number of authorized officer positions.

☞ Eliminate staffs, headquarters, and bureaucracies made unnecessary by the end of the Cold War and the drawdown in the size of the military from its peaks in the 1980s.

☞ Tighten the 1954 guidance on allocation of positions to military or civilian personnel to restrict use of officers in activities far from the central military mission of fighting wars.

☞ Convert administrative and other support positions from uniformed officer to civilian status wherever possible.

☞ Reject efforts to increase the current limit on the number of generals and admirals, and instead reduce it.

Since keeping more uniformed officers than are needed costs the military, the government, and the taxpayer millions of dollars every year, officers should be dedicated as much as is feasible to fighting wars, rather than administration and other marginal functions.

[1] See "Plan for 54 More Top Officers Puts Services on the Defensive," Walter Pincus, The Washington Post, April 9, 1997, p. A19.

[2] "Sheehan: Start by Cutting Staff Jobs," Jon R. Anderson and ERnest Blazar, Navy Times, September 16, 1996, p.8.

[3] "A General Disagreement," Walter Pincus, Washington Post, July 1, 1996, p. 15.

[4] "Marine Request to Add Generals Fans Hill Flames," Walter Pincus, Washington Post, July 19, 1966, p.25.

[5] "Active Duty Military Personnel: 1789 Through Present," Table 2-11, Selected Manpower Statistics Fiscal Year 1996, Department of Defense, Directorate of Information Operations and Reports.

[6] U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters, Marine Corps Historical Center, written communication, November 21, 1997.

[7] "Active Duty Military Personnel by Rank/Grade - March 31, 1997," Department of Defense, Directorate of Information Operations and Reports.

[8] General and Flag Officers: Number Required Is Unclear Based on DOD's Draft Report, General Accounting Office, NSIAD-97-160, June 1997, p.13.

[9] General and Flag Officers: Number Required Is Unclear Based on DOD's Draft Report, General Accounting Office, NSIAD-97-160, June 1997, p.3.

[10] General and Flag Officers: Number Required Is Unclear Based on DOD's Draft Report, General Accounting Office, NSIAD-97-160, June 1997, pp.3-4.

[11] "Is Military Top-Heavy with Staffs?," William Matthews, Navy Times, June 17, 1996, p.9.

[12] National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1998, P.L. 105-85, Sec. 506.

[13] Insert for the Record, Senate Appropriations Committee, Defense Subcommittee, FY98 Army Posture, April 16, 1997, p.1.

[14] General and Flag Officers: Number Required Is Unclear Based on DOD's Draft Report, General Accounting Office, June 1997, NSIAD-97-160, p.17.

[15] "Pentagon Detailees Dig In on Hill," Al Kamen, The Washington Post, August 7, 1996, p.17.

[16] "Pentagon to Review Hill 'Fellowships'," Dana Priest, The Washington Post, October 10, 1996, p.1.

[17] "Pentagon Detailees Dig In on Hill," Al Kamen, The Washington Post, August 7, 1996, p.17.

[18] "Senate Blocks Probe of Aides," Rowan Scarborough, The Washington Times, February 12, 1997, p.1.

[19] Review of Military and Civilian Personnel Assignments to Congress, Department of Defense Inspector General, Report No. 97-186, July 14, 1997, as summarized at http;//www.ignet.gov/ignet/internal/dod/97/dod7186.html

[20] Financial Management: Opportunities to Improve Experience and Training of Key Navy Comptrollers, General Accounting Office, May 1997, AIMD-97-58, pp.4-5.

[21] Ibid., pp.1-2.

[22] Ibid., p.14.

[23] DOD Force Mix Issues: Converting Some Support Officer Positiions to Civilian Status Could Save Money, General Accounting Office, October 1996, NSIAD-97-15, p.3.

[24] Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 1998 - Historical Tables, 1997, p.54.

[25] DOD Force Mix Issues, Converting Some Support Officer Positions to Civilian Status Could Save Money, NSIAD-97-15, General Accounting Office, October 1996, p. 10.

[26] General and Flag Officers: Number Required Is Unclear Based on DOD's Draft Report, General Accounting Office, NSIAD-97-160, June 1997, p12.

[27] "Services Need to Balance Their Assets - Sheehan," Greg Caires, Defense Daily, June 11, 1996. p. 423, and "Sheehan: Start by Cutting Staff Jobs," Jon R. Anderson and Ernest Blazar, Navy Times, September 16, 1996, p.8.

[28] DOD Force Mix Issues: Converting Some Support Officer Positions to Civilian Status Could Save Money, General Accounting Office, NSIAD-97-15, October 1996, p.2.

[29] Quality of Life for Air Force Personnel, insert for the redord to testimony of Secretary Widnall before the Senate Appropriations Committee, Defense Subcommittee, May 21, 1997.

[30] Insert for the Record, Senate Appropriations Committee, Defense Subcommittee, FY98 Army Posture, April 16, 1997, p.1.

Sent Saturdays