Dan Grazier

Author

At a recent House Armed Services Committee hearing, Lt. Gen. Arnold Bunch, a deputy in the Air Force’s acquisitions office, fielded a question from Guam Representative Madeleine Bordallo about the decision to use a riskier cost-plus contract rather than a fixed-price contract for the development phase of what is now being called the B-21 bomber. “When there is technical risk and you’ve never built something before, and there’s risk that’s out there, and a cost-plus environment is more frequently used in that case,” General Bunch said.

This seems at odds with the advertising and lobbying case Northrop Grumman made as it fought for the contract. Remember those flashy Super Bowl commercials touting the contractor’s experience building bombers? “This is what we do,” the narrator says. And based on the images provided by the Air Force, it appears Northrop Grumman is hardly developing a radically new design.

The Air Force awarded the bomber contract to Northrop Grumman in October 2015. And according to several sources, their previous experience building the B-2 likely factored heavily in the decision.

General Bunch’s comments during the hearing were oddly contradictory. Immediately after talking about the technical risk and suggesting a stealth bomber is a radically new concept in military aviation, General Bunch spoke of all the mature technology to be integrated into the new plane.

Contracting Choices

A cost-plus contract is used to reimburse a defense contractor for the allowable expenses of developing a weapon system, adding a fee on at the end for an incentive. It is a risky contracting vehicle because the temptation for contractors to spend freely during the design phase is great, knowing their expenses will be covered in the end. They may choose to purchase a $500 part over a $100 part, for example, simply because it was more convenient to do so. This is why careful management and rigorous oversight is critical. Unfortunately, the necessary level of careful oversight rarely occurs.

Senator McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has come out forcefully against using a cost-plus contract for the program. “Tell me one time that there hasn’t been additional costs, then I would reconsider,” McCain said recently. “The mindset in the Pentagon that still somehow [cost-plus contracts] are still acceptable is infuriating.” He also said if the contractors were not willing to accept the risk involved in the contract, they shouldn’t have bid on it in the first place.

Fixed-price contracts, which Senator McCain wants in this case, are not without their own risks. With a price set before the design has matured, companies have an incentive to cut costs to maximize their profit and potentially deliver an inferior product. Decision-makers must carefully balance these considerations as they make contracting decisions.

The type of contract used is important, but more important is how the contract is negotiated and the level of administration and oversight for the program. The taxpayers often end up shelling out more money beyond the fixed-price costs to repair manufacturing defects after a product has been delivered. The Government Accountability Office recently reported on a case of six ships that required extensive repairs to correct defects. The taxpayers ended up covering 86 percent of these costs—$6.4 million—because of the way the contract had been negotiated. The GAO says the Navy agreed to the cover the majority of repair costs in order to keep the price to build the ships down. “This means the Navy and Coast Guard paid the shipbuilder to build the ship as part of the construction contract, and then paid the same shipbuilder again to repair the ship when defects were discovered after delivery—essentially rewarding the shipbuilder for delivering a ship that needed additional work.”

The manner in which the program is funded could also determine the ultimate cost. Officials have hinted at the possibility of creating a separate fund to build the new bomber in the same way the Navy convinced Congress to establish a “National Sea-based Deterrence Fund” to build a replacement for the Ohio-class ballistic missile. By allowing the Air Force to build the bomber with funds outside of its normal construction budget, there would be much less incentive to control the program’s costs. The Air Force is signaling they want to declare this program a “national” asset. The special fund would be run by the Secretary of Defense while the Air Force would still keep its normal weapons buying budget. The Air Force would essentially get someone else to buy its newest plane, rather than having to budget for it accordingly with the rest of its acquisition programs.

Senator McCain says he wants the Air Force to tell the taxpayers exactly how much the program is going to cost. Air Force officials did release a document with the results of an independent cost estimate in October that put the development costs at $23.5 billion. General Bunch said this figure is higher than the actual contract, but would not provide any further details.

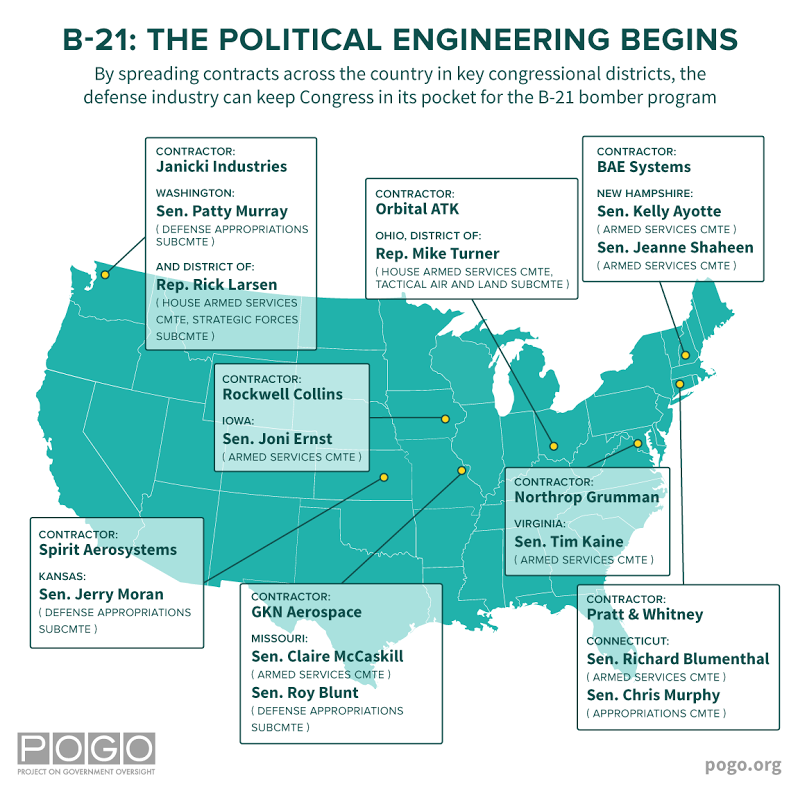

The Political Engineering Begins

While the debate about the contract has been quite public, little else about the project has been. That is because most aspects of the program have quite appropriately been classified. This makes the recent public announcement of subcontractors troubling. If the program is classified for national security reasons, then the entire program should be secret to include the list of subcontractors.

Air Force Secretary Deborah James and Chief of Staff General Mark Welsh listed seven companies who will build components for the new plane at a state of the Air Force press conference. They didn’t provide many details as to what those contributions will be, but a quick look at the history of the companies provides some indication of how this project will be built. It also shows the program is being designed to have broad political support by spreading the work across numerous states and congressional districts.

Veteran military reformer Franklin “Chuck” Spinney describes political engineering as “business as usual” for programs of this kind. “By designing overly complex weapons, then spreading subcontracts, jobs, and profits all over the country, the political engineers in the Defense Department deliberately magnify the power of these forces to punish Congress, should it subsequently try to reduce defense spending by terminating major procurement programs.”

The companies made public so far are BAE Systems, GKN Aerospace, Janicki Industries, Orbital ATK, Rockwell Collins, Spirit AeroSystems, and Pratt & Whitney.

BAE Systems plant in New Hampshire is the headquarters of the company’s electronic systems division. There they produce electronics for “flight and engine control, electronic warfare, surveillance, communications, geospatial intelligence, and power and energy management.” Both U.S. Senators for New Hampshire, Jeanne Shaheen and Kelly Ayotte, serve on the Senate Armed Services Committee.

GKN Aerospace’s St. Louis plant specializes in building structural components like the main fuselage and wing assemblies. They also build canopies for fighter jets and cockpit glass for larger planes. Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri serves on the Senate Armed Services Committee while Senator Roy Blunt serves on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee.

Janicki Industries builds aircraft pole models for developmental testing (for instance, the company built full-scale replicas of the F-35 to be used for Radar Cross Section testing to determine how that plane’s shape would appear on radar screens). The company has 700 employees spread across three plants in Washington and Utah. Washington Senator Patty Murray serves on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. Representative Rick Larsen’s Washington district is home to Janicki Industries headquarters. He is a member of the Armed Services Committee and sits on the Strategic Forces subcommittee.

Orbital ATK previously worked with Northrop Grumman on the B-2 by building low-observable antennas for that stealth bomber in its Dayton plant. The company currently builds wing coverings, engine housings, and inlet ducts for the F-35. This plant is in the district of Representative Mike Turner, a member of the House Armed Services Committee. He chairs the Tactical Air and Land subcommittee, which has oversight of Air Force acquisition programs.

Rockwell Collins largely focuses on avionics. They build communications and navigation systems as well as heads-up displays for virtually all NATO military aircraft flying today. Their components are integrated into all three of the current bomber aircraft. The company is headquartered in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Senator Joni Ernst serves on the Armed Services Committee.

Spirit AeroSystems has largely focused on providing large fuselage assemblies for commercial airliners, but has recently worked to expand its business into defense contracts. The company builds the forward fuselage for the KC-46 air refueling tanker and the main fuselage for the Marine Corps’ new CH-53K heavy lift helicopter. The company is headquartered in Wichita, Kansas. Senator Jerry Moran serves on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee.

Pratt& Whitney will build the engines for the new plane at its East Hartford, Connecticut, plant. Its engines are already flying in in the F-35, F-22, the C-17 Globemaster III, and several other military planes. Senator Richard Blumenthal serves on the Armed Services Committee while Senator Chris Murphy serves on Appropriations.

Northrop Grumman itself is headquartered in Falls Church, Virginia. Senator Tim Kaine serves on the Armed Services Committee.

A complete understanding of the how the new bomber will be built is still many years away. Still, as the little information publicly available now shows, the DoD and the defense industry is still using the same old political tricks. By publicly announcing some of the program’s subcontractors, officials have tied the program to specific congressional districts, making it difficult for Members of Congress with plants in their districts to oppose or criticize the program for legitimate military and budget reasons without also seeming to act against their districts’ interests.

Just another typical day in Washington.

Sent Saturdays