Mark Thompson

Author

Amazing to stride several yards and go from shards of Abraham Lincoln’s head into the minds of today troops roiled by our nation’s post-9/11 wars. But that’s the kind of strange battlefield bazaar the Pentagon’s National Museum of Health and Medicine is. Tucked deep in the Maryland woods just north of Washington are pieces of military history far removed from combat. But war is rendered real here in ways unlike anywhere else.

It’s fair to think of the U.S. military like a solar system, with its Sun its war-fighting ranks. But that’s only about 10% of the total force. The planets closest to that Sun—the combat enablers who keep the tanks running, airplanes flying and ships sailing, are the Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars of this peculiar universe. The planets further from the Sun—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and (in some quarters) Pluto—are the folks who keep the U.S. military, if not its machines, humming: lawyers, chaplains, public-affairs officer and medics among them.

They rarely get due credit for their vital missions. So let’s shine a light on the military’s medical community by focusing on a rarely-visited facility, far removed from the Smithsonian-packed National Mall, that that celebrates their work. Now located in Forest Glen, Maryland, it spent years at the now-shuttered Walter Reed Army Hospital in the capital. It moved to suburban Maryland four days after 9/11. A memorial outside the museum honors Lieut. Colonel Karen Wagner, a personnel expert who was the only Army Medical Department officer killed on 9/11, one of 188 who perished when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon.

The museum has about 25 million items—among them some 5,000 skeletal specimens, 8,000 preserved organs, and 12,000 pieces of medical gear—that rotate in and out of its constantly-changing exhibits. It houses a wealth of information on, among other things, medicine during the Civil War, the challenge of identifying war remains, the Iraq war’s Balad Theater Hospital, which saved countless lives, and curiosities like conjoined—Siamese—fetuses. Human organs are “plasticized” and displayed to the awe, and sometimes revulsion, shared by old and young alike.

Perhaps the most chilling exhibit has to do with the assassination of President Lincoln 152 years ago. Nothing brings his murder into sharper focus than pieces of his skull, the bullet that felled him, and the blood-stained cuffs of the Army doctor who conducted the autopsy.

“His wound is mortal,” Charles Leale, a second Army doctor who was attending Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865, said after rushing into the Presidential Box and examining his comatose commander-in-chief. “It is impossible for him to recover.”

Nine hours later, Lincoln was dead.

While there are exhibits on the trauma of war, there’s also a lot dealing with disease, notably yellow and typhoid fevers, which used to kill many more soldiers than it does today. Better battlefield medicine has boosted a wounded soldier’s odds of survival from roughly 90% in Afghanistan and Iraq, up from the Vietnam War’s 85% and World War II’s 80%.

But the ravages of war on soldiers’ minds remain a persistent problem. These are the kinds of stories that stick in your mind if you have been covering U.S. troops since 9/11:

— The Army’s desperate push to calm soldiers’ fears and anxieties by plying them with pills.

— The service’s effort to hire enough mental-health professionals to ease its soldiers’ PTSD-racked brains.

— A sergeant who came home with headaches caused by the explosion of an IED near Baghdad who ended up dead while under the Army’s care.

— The killing of legendary sniper and Navy SEAL and Chris Kyle at the hands of a battle-scarred Marine he was trying to help.

— The death of an American family after their soldier returned from war.

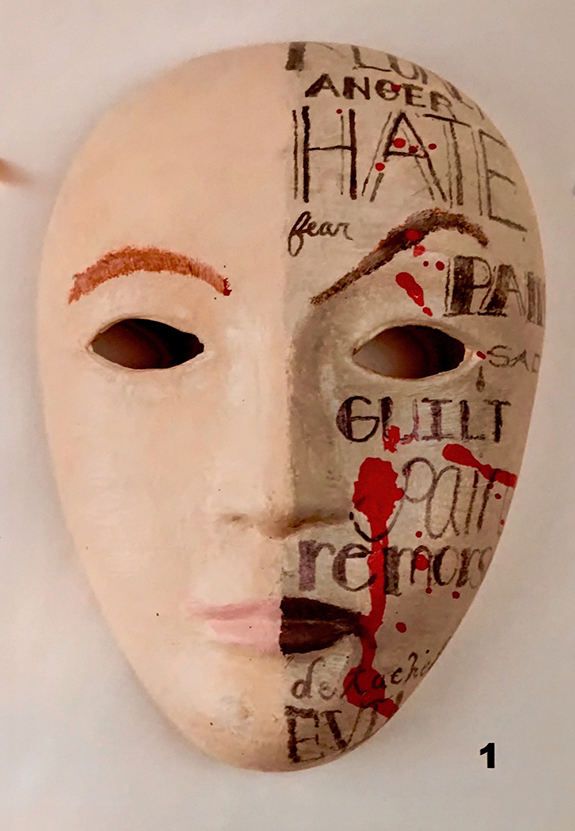

Trying to reduce the pain of such losses is the focus of a poignant new exhibit at the museum (free, and open every day except Christmas). While the bulk of its collections consists of actual medical specimens and historical artifacts, this one is different: it is freshly-created self-portraits done by troops troubled by post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injuries suffered in Afghanistan and Iraq. “This display of work and art are the Veterans' processing of loss of friends and identity/guilt/grief, and a multitude of other struggles war and combat have placed upon them,” the exhibit notes.

Like other attempts to weed out the demons of war—beyond pills and psychiatric treatment they include dogs and the creation of the nation’s first-ever brain bank for PTSD—progress can be slow and halting. Such art therapy has two goals: to help ailing vets heal by wringing out the deep anger and anxiety they’ve brought back from the front lines, and to show the rest of us just how deep and pernicious some of these “invisible wounds” of war can be for some combat veterans.

"I can say from my own experience that not all treatments are equal," Army Sgt. Timothy Goodrich told the exhibit’s organizers. "I truly thought there was no road home for me. The day I turned back was the day I surrendered to the process of art therapy."

Strange. Sometimes a soldier has to surrender in order to win.

Sent Saturdays