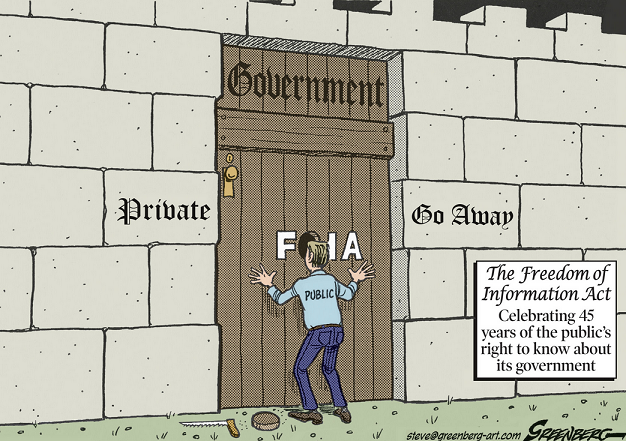

SUNSHINE WEEK: Many Agencies Violate FOIA's 20-Day Requirement

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is one of the most powerful tools to pry public information out of the federal government. But while FOIA requires agencies to respond to a request for information within 20 business days, an analysis of a recent batch of POGO FOIA requests shows that many agencies are violating the law by failing to meet even this basic requirement.

Between February 3 and 6—over 20 business days ago—POGO submitted 100 FOIA requests for work done by federally contracted consultants. POGO requested a specific written report or briefing produced by contractors hired as consultants to federal agencies as well as the respective statement of work—all from named contracts. POGO submitted the requests to 30 different agencies and departments.

To date, agencies have failed to acknowledge receipt of or respond to 23 of these requests. The following agencies have not sent an email or letter responding to POGO’s request: the Department of the Treasury; the IRS; the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement (BOEMRE); Defense Finance and Accounting Services (DFAS); and the Department of Justice (DOJ). Three FOIA offices—those of the Army, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Department of Energy (DOE)—have acknowledged some but not all of the requests POGO sent to them.

POGO received only 8 final, conclusive responses to FOIA requests within 20 business days. But in five of those cases, the agencies told POGO that after a search there were no documents that could fulfill the request. POGO received two additional responses shortly after the 20-day mark.

The 20-day minimum requirement for acknowledgement under FOIA is a low bar, but in this case, it was a bar that agencies couldn’t clear in nearly one out of four requests.

This batch of requests also shed light on agencies’ use of extensions.

Excessive use of extensions?

Though FOIA requires agencies to provide a final response within 20 business days, agencies can meet this requirement without actually giving a requestor what he wants by acknowledging a request or extending the 20-day deadline. FOIA allows agencies to extend the 20-day deadline in the event of unusual circumstances. In POGO’s case, however, requests for extensions were far from unusual. Thus far, POGO has received 26 requests for extension (again, POGO initially submitted 100 FOIA requests).

POGO realizes that the FOIA process involves many people and many different offices. After a FOIA request leaves POGO’s hands, there are plenty of officials involved—often times a general FOIA officer, a program officer, a contract officer, legal department, and possibly the contractor will all review a request and response before any record is sent to the requestor.

Even so, the justification for these extension requests didn’t always seem to hold water. One Pentagon FOIA officer wrote that the Defense Department (DoD) “will be unable to respond to your request within the FOIA’s 20 day statutory time period as there are unusual circumstances which impact on our ability to quickly process your request.”

What are these unusual circumstances? DoD cited “the need to search for and collect records from a facility geographically separated from this Office”; “the potential volume of records responsive to your request”; and “the need for consultation with one or more other agencies or [Department of Defense] components having a substantial interest in either the determination or the subject matter of the records.” The General Services Administration also cited volume, adding the request “may be larger in volume than previously anticipated.” And in a similar extension request, the Federal Aviation Administration called the requested records “voluminous.”

But the requests for an extension based on the “potential volume of records” doesn’t seem to apply to POGO’s fairly narrow request for two records, each of which related to a specific, named contract: one statement of work for that contract to generate a report, and the report itself.

Furthermore, the notion that FOIA requests should be delayed because of the geographical separation of offices doesn’t seem persuasive, as documents are often stored electronically and can be scanned in if necessary. This and other letters telling POGO that agencies need more than 20 days appear to be generic, as opposed to letters with specific analysis relevant to each individual request.

Backlogs could lead to excessive extensions

One reason why agencies may rely on extensions is the vast backlog of FOIA requests. Some FOIA offices have requests dating back to the 1990s. Currently, backlogs among the ten busiest FOIA offices are often huge; for example, according to FOIA.gov, the Department of Homeland Security had over 42,000 backlogged requests at the end of fiscal year 2011. At the same time, the Department of Defense had over 7,000 backlogged requests and the Department of Health and Human Services had over 6,000 backlogged requests.

The Obama Administration’s Open Government Directive required agencies with a significant pending backlog of outstanding FOIA requests to “take steps to reduce any such backlog by ten percent each year.” In order to reduce backlogs, FOIA offices may have to sacrifice processing times and, as a result, issue too many extensions.

Bigger picture

So how does the dismal response rate to POGO’s batch of requests compare to the overall picture? According to FOIA.gov, 70 percent of FOIA simple requests and 43 percent of complex requests in the 10 busiest FOIA offices in FY 2011 were processed with a final response within 20 days:

| Rank | Department | Simple Requests Processed | Simple Requests Processed in 1-20 Days | % of Simple Requests Processed in 1-20 Days | Complex Requests Processed | Complex Requests Processed in 1-20 Days | % of Complex Requests Processed in 1-20 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Homeland Security | 64,895 | 38,147 | 58.8% | 64,792 | 12,366 | 19.1% |

| 2 | Department of Defense | 44,797 | 37,934 | 84.7% | 26,492 | 13,781 | 52.0% |

| 3 | Department of Health and Human Services | 57,296 | 42,293 | 73.8% | 12,702 | 4,875 | 38.4% |

| 4 | Department of Justice | 46,469 | 29,539 | 63.6% | 10,169 | 3,432 | 33.7% |

| 5 | Social Security Administration | 31,796 | 28,616 | 90.0% | 649 | 422 | 65.0% |

| 6 | Department of State | 17,324 | 1,356 | 7.8% | 5,491 | 29 | 0.5% |

| 7 | Department of Veterans' Affairs | 171 | 171 | 100.0% | 27,961 | 22,223 | 79.5% |

| 8 | Department of Agriculture | 16,948 | 15,446 | 91.1% | 2,008 | 904 | 45.0% |

| 9 | Department of Labor | 8,822 | 7,172 | 81.3% | 9,077 | 6,147 | 67.7% |

| 10 | Department of the Treasury | 2782 | 2,479 | 89.1% | 13525 | 9977 | 73.8% |

| Total | 291,300 | 203,153 | 69.7% | 172,866 | 74,156 | 42.9% |

The Department of Veterans Affairs, to which POGO sent 3 requests regarding 3 specific contracts, has both the highest rate of simple and the highest rate of complex requests processed within 20 days at 100 percent and 79 percent, respectively. On the other hand, the Department of State—where POGO sent 3 requests—has the lowest rates of response within 20 days for both simple and complex requests at 8 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively.

In contrast, POGO has only received final responses in 8 out of its 100 requests within 20 days (with 2 more responses coming in after the 20-day mark)—a response rate that is far lower than both the 70 percent average for simple requests and the 43 percent average for complex requests at the top 10 FOIA agencies. Again, POGO’s requests do not seem especially complicated—POGO only sought two government records in each request.

What does it all mean?

On the whole, reviews of the Obama Administration’s efforts to improve FOIA administration have been mixed: FOIA backlogs have come down, but the accuracy of backlog reduction figures have been called into question, and there are reports of some requests being closed without requestors being notified. Meanwhile, FOIA processing times for certain agencies have improved, but agencies’ use of FOIA exemptions to withhold information is up.

POGO’s batch of requests offers another piece of evidence showing that there’s still plenty of room for improvement when it comes to FOIA administration. Agencies shouldn’t abuse their ability to extend the 20 day deadline—and at the very least, agencies should be able to follow the law and acknowledge receiving a request within 20 business days.

-

Andrew Wyner

Oversight in your inbox

Sent Saturdays