Could a Pricey Federal Project Worsen Racial Inequities in Mississippi?

A troubling percentage of those surveyed can’t say whether extremism directives prohibit service members from violating people’s constitutional rights or donating to racist groups.

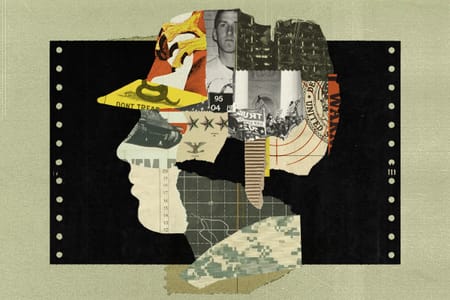

(Photos: Getty Images; Brett Davis / Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0, Modified; National Archives; Department of Defense; Illustration: Leslie Garvey / POGO)

A number of Army personnel believe anti-extremism directives don’t prohibit service members from violating people’s constitutional rights or donating money to explicitly racist groups, according to a previously unreported 2023 Army report.

One in 10 who participated in a survey inside the U.S. Army “didn’t identify using force, violence, or unlawful means to deprive individuals of their rights under the U.S. Constitution as an extremist activity” that is prohibited by Army rules. That and other findings come, in part, from 417 Army personnel who responded to a survey, according to the Army Audit Agency report, obtained by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO) through the Freedom of Information Act.

Twenty-one percent “didn’t identify donating money to a group advocating the superiority of one racial group as prohibited behavior,” according to the report.

The Army’s policy on extremism identifies numerous activities as prohibited, including “the use of force or violence or unlawful means to deprive individuals of their rights under the United States Constitution or the laws of the United States, or any State.” It also cites participating in a group or activity that advocates “racial, sex (including gender identity), sexual orientation, or ethnic hatred or intolerance,” including fundraising for these kinds of groups.

“Military personnel must reject participation in extremist organizations and activities,” the Army policy states.

“These new, previously unreported findings add to a growing number of data points that suggest there is both a heightened concern of extremism and insufficient awareness about what constitutes extremism inside the U.S. Army.”

The Army Audit Agency report was based on a survey of respondents who were either uniformed service members, including those in the National Guard and Reserves, or civilian federal employees, as well as focus groups and interviews. The report does not say what share of survey respondents were in uniform and what share were civilian employees; all are required to report “matters of concern,” according to Pentagon policy.

These new, previously unreported findings add to a growing number of data points that suggest there is both a heightened concern of extremism and insufficient awareness about what constitutes extremism inside the U.S. Army, despite efforts to prevent and stop these activities in the military.

In addition to the number of respondents who failed to identify prohibited extremist activities, the audit showed that many who could identify extremism did not know how to report it. The audit report found that 43% “incorrectly identified their reporting channel for extremist behavior” and 36% “were uncertain about the reporting channel.”

“Soldiers’ and civilians’ inability to recognize or report extremist activities or indicators of extremist behavior reduces the Army’s ability to address inappropriate behavior before it damages unit cohesion and readiness and tarnishes the Army’s reputation,” according to the report. “If action isn’t taken, the Army could miss opportunities to intervene before inappropriate behavior becomes a prohibited support of an extremist organization.”

However, “most of the 417 respondents to our survey agreed their unit emphasized extremism prevention and awareness and took the topic seriously,” states the report. Some 77% responded in the affirmative when asked whether their “unit takes allegations of extremism very seriously and responds (or would respond) to reports of extremist activity promptly.”

“The audit showed that many who could identify extremism did not know how to report it.”

The report found that many Army commands had taken action to address concerns about extremism in the ranks. “Four groups said their commanders held open-ended conversations and training after the events of 6 January 2021 at the U.S. Capitol,” according to the report. But commanders were in the dark about training tools the Defense Department had developed. “Commanders we interviewed weren’t aware of this instruction and training or that they could use training materials from military equal opportunity professionals to educate Soldiers proactively on extremism,” the report says. “For this reason, commanders developed their own extremism training.”

There are about 940,000 soldiers in the U.S. Army, 440,000 of whom are active duty, with the others split between the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve, according to December 2023 Pentagon data. There are about 229,000 civilian Army employees. The survey, which had a 36% response rate, was sent to 1,158 people. The audit report notes that the sample was “nonstatistically selected” and therefore, “our results can’t be projected across the Army.” Yet there are a number of troubling data points suggesting there is a greater problem in the Army than the other military services.

Of all the armed services, persons who have served in the Army are the most represented among defendants charged with January 6-related crimes, according to an analysis by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. That analysis found that, out of 209 defendants who enlisted in the U.S. military, 73 served in the Army, 24 in Army National Guard units, and 15 in the Army Reserves. The vast majority were not serving on January 6, 2021.

“One key problem is that there is substantial confusion regarding what extremist behavior is.”

Despite the confusion some in the Army have regarding reporting extremist activities, many within the Army are making disclosures. A Pentagon inspector general report published in November 2023 contained data showing that the vast majority of formal allegations of extremism in fiscal year 2023 came from the Army: 130 out of 183. A substantial number of those claims involved allegations of anti-government extremism. Of the 130 claims, 56 were regarding “advocating for, engaging in, or supporting the overthrow of the U.S. Government or seeking to alter the form of the Government by unconstitutional or other unlawful means.”

While a Pentagon-commissioned Institute for Defense Analyses study released in December did not find a disproportionate extremist threat inside the military compared to the country at large, it stated that “the participation in violent extremist activities of even a small number of individuals with military connections and military training, however, could present a risk to the military and to the country as a whole.” Groups like the Oath Keepers — which saw several of its leaders convicted for seditious conspiracy or other crimes connected to the January 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol — have actively sought to recruit current service members and veterans.

One key problem, the June Army audit found, is that there is substantial confusion regarding what extremist behavior is. “Inconsistent definitions caused personnel we interviewed and surveyed to be unsure of what was and wasn’t extremist behavior,” the report states. In 11 of the survey’s 27 focus groups, participants said the Army’s definition “was too long, confusing, or the different definitions made it harder to understand extremism.” One participant asked, “Where is the line between racism and extremism? Or is racism extremism?”

After the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, the Department of Defense updated its rules in December 2021 to better define extremist activities, but according to the recently released Institute for Defense Analyses study, “even with the update, ambiguities persist and further guidance is needed to standardize practices for identifying cases of prohibited extremist activities.” While there is still room for improvement at the Pentagon, the Army has lagged further behind. The Army said that it will issue a new extremism policy with a better definition by the end of the second quarter of fiscal year 2024, which is next month.

The problem itself is not new. In the wake of the 1995 bombing of the FBI building in Oklahoma City that killed 168 people, it did not go unnoticed that the perpetrators of the attack, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols (and a third accomplice), met and served together in the Army. Oklahoma City remains the deadliest domestic terrorism attack in U.S. history.

That same year, white, active-duty soldiers murdered two Black people in North Carolina, who they picked randomly due to their race. The white supremacist views of one of the murderers was apparently “well-known” prior to the murders, according to a Washington Post article, underscoring why identifying and reporting extremist activity before there is violence is so important. The then-secretary of the Army launched a task force on racial extremism.

Then, like now, there were questions about how to define extremism and how to mount an effective approach to identifying extremists in the ranks. Yet “no clear definition of ‘extremism’ was established” by the task force, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank. Even if January 6 was a “wake-up call,” as then-Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby said in 2021, last year’s Army audit shows there is still a long way to go, especially amid recent reports that the Pentagon’s anti-extremism efforts have stalled.

Sent Saturdays