Peter Tyler

Author

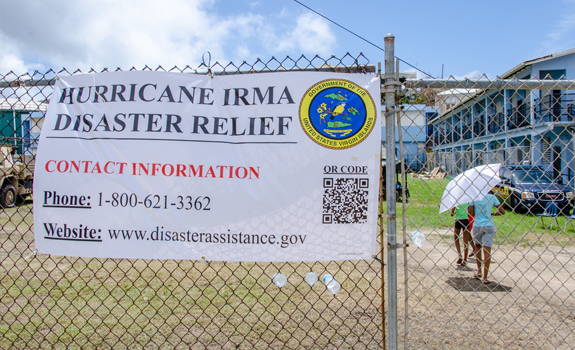

This year has seen many tragic firsts for national disasters. Four major hurricanes came ashore within six weeks in the Gulf and Caribbean, setting a new and staggering record. The resulting disasters affected millions of people who were living in the paths of the storms, causing death, injury and illness, and destroying or damaging homes and businesses. An estimated 3.5 million people have registered for federal disaster assistance so far this year.1

The devastation will be long-lasting in a large number of American communities along the Gulf Coast and on the Caribbean Territories. Many homes and buildings are still at the beginning stages of repair, and Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands face months before a majority of people have power and clean water in their homes and communities. And the hurricanes are not even the whole story. The deadliest wildfires in California history struck in October, killing dozens and wiping out whole neighborhoods. Additional disasters were declared for floods, fires, and other events across the nation, which, though smaller in terms of destruction, still had a devastating impact on the local communities.

The responses by survivors, their neighbors, and emergency responders were heroic. Press accounts describe rescues, neighbors helping neighbors, and exhausted first responders and aid workers providing life-saving assistance.

The questions the nation needs to ask now are whether we were as prepared as we needed to be, and if there are any lessons to learn in preparation for future major disasters. The short answer to these questions: no, we were not as prepared as we should have been, and yes, we can and must learn from the 2017 disasters.

Clearly, there are lessons for Congress and the White House to learn. It seems that after every major disaster comes the realization that a response to major disasters costs money. And every few years, Congress, led by those representing the affected states, arrange for additional billions of dollars in funding. These “emergency” funding bills are separate from the normal budgeting process. Partly, this is a budget procedure trick to avoid having to treat disasters as predictable expenses that are part of costly budget scoring and planning. However, this results in a slowed recovery due to financial uncertainties and politicization of disasters.

Preparing for major fires, storms and earthquakes should be part of the normal functions of government. We as a nation must recognize that large disasters are no longer uncommon, and while the specifics may be unpredictable, the response shouldn’t be.

First, let’s put the recent disasters into perspective.

Both the quantity and severity of 2017 disasters are historically noteworthy. Ten Atlantic hurricanes formed this year, the first time we saw that number in more than a century. And of the four that reached U.S. soil, one—Irma—reached Category 5, the highest level.2 Maria (also having earlier reached Category 5) and Harvey both made landfall as Category 4. Smaller in strength only by comparison, Nate made it to a Category 2 level.

Did we as a nation do enough to prepare and respond to the disasters? Unfortunately, the answer by the U.S. government’s own metrics is no. FEMA had a goal of “restoring basic services and community functionality” within 60 days, focused on “essential city service facilities, utilities, transportation routes, schools, neighborhood retail business, and offices and other workplaces.”3 This was a goal that we did not reach in Puerto Rico or the Virgin Islands.

Will the severity of the disasters of 2017 be equaled in years to come? Yes. The better question is not will hurricanes happen, but how many and how devastating will they be? Wildfires will also continue to happen with what is looking like an expanding length of the season.4 Earthquakes, tornadoes, tsunamis, and other disasters strike with even less advance notice, and also result in great destruction.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tracks the cost of U.S. weather-related disasters, and the trend of greater and costlier damage is clear.5 The number of billion-dollar hurricane disasters in 2016 was the second highest, behind 2011. Looking more long-term, the average number of such disasters has doubled since 1980. And the four 2017 hurricanes—Harvey, Irma, Maria and Nate—are expected to hit a new annual monetary damage record—$200 to $300 billion. For comparison, the previous record was set by Hurricane Katrina at $161 billion (inflation adjusted). The 2012 Sandy hurricane total was $70 billion (inflation adjusted).6

The increase in disaster costs cannot be dismissed as mere chance, or an uncommon problem during a few unlucky years. Weather and climate are not the only factors resulting in an increase in damage costs. Rising population and development patterns—more people and buildings in disaster areas—are the other factors. But for whatever the reason, the numbers and trends are clear.

So what has 2017 taught us? First, strong government leadership in disaster response is key.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the lead response agency in preparing for, and responding to, the nation’s disasters. Having well-trained, experienced and dedicated staff at all levels is critical. You can’t outsource emergency response, nor can the nation simply wait for a disaster to get our act together.

Of course, in a disaster, every hour counts. Disaster experts point out that by the time a disaster happens, it is too late to start figuring out the response. Planning and working together before a disaster is crucial for the agencies. And as hurricane disasters from Katrina to Maria showed us, disasters require preparation months and years in advance.7 Local responders and leaders do not have time to put together a plan when disaster is looming—this is when contingency plans are put into operation. This is even truer for a “no-notice event,” such as an earthquake. Without proper planning, federal agencies, including the military, would show up late or ill-prepared.

The good news is that, since Katrina, FEMA’s disaster preparation and response mission has received much more attention. FEMA’s leaders are generally people who are disaster and emergency response professionals, not just political appointees who learn the ropes after appointment. The current FEMA administrator, Brock Long, came to FEMA after having led Alabama’s emergency management agency.8 And his predecessors in the last administration came with similarly strong backgrounds, such as former Administrator Craig Fugate, who headed Florida’s disaster agency.9

But FEMA does not, and cannot, do the job on its own.

State and local governments play a key role, both in preparing for and responding to the disasters in their collective backyards.

Equally important, FEMA operates much of the federal response in coordination with other federal agencies. FEMA’s National Incident Support Manual10 describes how an operation is supposed to unfold. FEMA puts forward the “mission assignments” to get “resources” —the equipment, supplies and trained people—to the scene. FEMA has trained staff and supplies ready to go. But FEMA largely works through “mission assignments” to its federal partners in order to get enough resources for an effective response. When FEMA wants to send generators, food, or medical teams, they make the requests to the specific federal agencies with those particular resources. The Department of Defense has transportation assets such as Army trucks and Air Force cargo planes, Health and Human Services has the medical teams, and so on. And FEMA will ask for them.

But FEMA cannot give orders to other agencies, only requests. That means working through the bureaucracies. In the past, even though representatives of the agencies work together, there have been disagreements among the bureaucracies.

More good news: since Katrina, federal agencies are required by law to formally prepare and practice their responses and how they work together. Every two years, the federal government tests the agencies’ responses to disaster with the “National Exercise Program.”11 The officials responsible for coordinating are brought together in a room, and a scenario is played out. In 2014, it was an Alaskan earthquake, and in 2016 the exercise focused on major acts of terrorism.

Hurricane Sandy in 2012 became the recent example of a real world response to a national disaster. Hurricane Sandy was the second-largest Atlantic storm on record when it made landfall in southern New Jersey. It knocked out power for more than eight million people and caused tens of billions of dollars in damage. During the response and recovery phases, President Obama established an ad hoc interagency Energy Restoration Task Force to find ways to restore power and ensure that the federal agencies effectively work together. One problem identified during the Sandy recovery was getting a large enough number of specialized power line repair trucks, such as the “cherry pickers” used to reconnect the power lines. Many could simply be driven in across state lines, but FEMA also needed air support. Due to the work of the interagency task force, the Pentagon delivered 229 vehicles by air.12

One conclusion of the “Sandy FEMA After-Action Report” is the need to “prepare for incidents that are larger and more complex.”13 The July 1, 2013 after action report was clear: “FEMA recognizes that it must plan for even larger, more severe storms and disasters.”14

The National Exercise Program continues to identify disaster response problems and note the lessons learned. In fact, the Department of Homeland Security keeps track of gaps in the response preparations. However, more can be done to apply the lessons learned. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted that implementation of corrective actions is not well-tracked. As a result, DHS and FEMA “cannot provide a comprehensive picture of the status of national preparedness.”15

The large and devastating Hurricane Katrina and our nation’s response to it sparked a much-needed debate over the response to major disasters. In 2006, Congress passed the Post Katrina Emergency Response Act,16 which updated critical laws and policies. Based on the work of congressional special investigative committees that examined the aftermath, the law helped define the interagency goals and preparations for major disasters.

FEMA has a critically important requirement: prepare for a major disaster—often with little or no warning—and assume the likelihood of “cascading effects,” where one disaster can create others. It is no longer adequate for the federal government to prepare for an earthquake; instead, it must expect that it can lead to a dam breaking or a nuclear power plant leaking radiation.17

The Japanese Fukushima disaster—or more correctly disasters—illustrates what FEMA means. On March 11, 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck Japan.18 The resulting, deaths and injuries, and major damage to buildings, roads and other infrastructure in Japan was bad enough. But the earthquake triggered a 10 to 40 meter high Tsunami that struck the coast.

More than fifteen thousand people perished and hundreds of thousands lost their homes, but then the situation took an even more catastrophic turn. Several of the country’s reactors suffered damage and fell victim to electrical power outages causing a partial nuclear meltdown and radioactive contamination.

The multiple disasters happening concurrently was not something for which Japan was well-prepared. But this cascade of disasters will no longer prove atypical.

It is time to up our game.

The last two months of U.S. disasters continues to stretch our response resources. Preparing for one major disaster is simply not good enough. The nation should assume multiple disasters within a short space of a few weeks or days is the new normal. If we don’t prepare now for more and larger-scale disasters, we simply will not be ready to act effectively when they happen.

The Executive branch has more to do to truly prepare for the new normal of major disasters. Smarter planning, with an eye on larger, more constant and cascading disasters, is a start. It also means closer cooperation among the federal agencies who respond to disasters.

The cost of getting ready for disasters is not necessarily going to break the bank. For example, an audit by the GAO put the annual cost of the ten FEMA centers responsible for storing and supplying basic items like bottled water and medical kits at about $65 million a year.19 FEMA and the disaster response community should determine whether this stockpile is still adequate. Not only is this an issue of adequate quantities, but also whether additional types of items that may be needed, such as in the likely scenario of electrical power outages.

Just providing more money will not solve everything, but what the recent trend in the cost of disaster recovery efforts tells us is we are not setting aside nearly enough money to help the impacted communities. Rather than recognize that multiple, large disasters are a major risk each year, Congress has chosen not to allocate in advance the needed amount of funds.20 This affects interagency planning and preparations that disaster professionals describe as critical.

After disasters strike, even with lawmakers from the disaster areas pressing for recovery monies, the budget process faces delays, with allocation decisions often put off for days or weeks after disasters occur. This month, 35 days after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, Congress passed a $36.5 billion hurricane relief bill with funding for these and other areas impacted by this hurricane season.21

Good stewardship over the billions of dollars in spending also demands more consistent oversight resources and attention. Whether agency spending for federal employees on the ground, contracting, or assistance and benefits to individuals, the upsurge in spending is at risk of waste and fraud. Auditing and oversight takes resources, and the interagency aspect of disaster response adds new complexity. Increases in disaster spending should include new funds for Inspectors General and the GAO to perform their oversight. However, oversight cannot ramp up as quickly as disaster spending, so Congress needs to include oversight budgeting on a regular basis

Congress, the White House, FEMA, and other executive branch agencies need to accept that multiple, catastrophic disasters is the new normal. More realistic budget submissions should reflect the actual cost of recovery and the need for more comprehensive preparations.

Despite clear trends, the federal government continues to plan for catastrophic disasters the way it always has—allotting some portion of funds that are never enough, failing to certify the readiness of the infrastructure, and only planning for one major disaster at a time. We can no longer operate this way, and the federal government needs to recognize that the increased frequency of hurricanes, floods, fires, and droughts is the new normal. American lives count on it.

Sent Saturdays