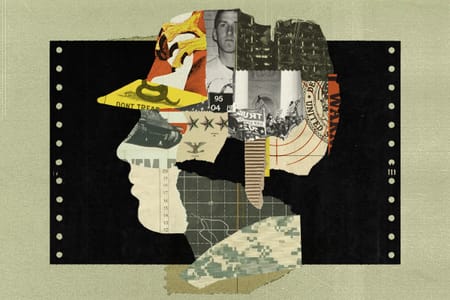

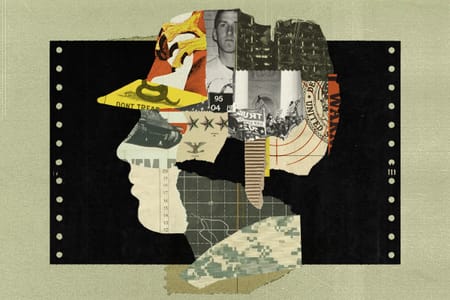

Army Struggling to Spot and Report Extremism, Audit Shows

Our new investigation.

Delivered to our subscribers on Thursdays, the new version of The Bridge is an email exclusive product that wades through the jargon of our government and gets straight to the key insights. Sign up here.

Anti-extremism rules are part and parcel of the U.S. Army’s general command policy. Under that guidance, soldiers are prohibited from engaging in a range of extremist activities — “using force, violence, or unlawful means to deprive individuals of their rights under the U.S. Constitution,” for example, or “participating in extremist organizations or activities” including those that “advocate ... racial, sex (including gender identity), sexual orientation, or ethnic hatred or intolerance.”

But we recently got our hands on an audit that revealed a troubling gap in Army personnel awareness of these guidelines. In a survey of several hundred Army personnel, including uniformed service members and civilian federal employees, 1 in 10 respondents didn’t identify violating an individual’s constitutional rights as a prohibited behavior. And 2 out of 10 respondents didn’t identify donating money to white supremacist groups as prohibited, either. Among those surveyed who did know these activities were prohibited, there were many who didn’t seem to know how to properly report extremist incidents.

The results of this survey are a glimpse of a bigger picture: the Army’s decades-long struggle to define, identify, and effectively root out extremism in its ranks. As POGO Senior Investigator and Bridge regular Nick Schwellenbach explains in his investigation, unheeded warning signs have, in the past, led to really terrible consequences.

“In the wake of the 1995 bombing of the FBI building in Oklahoma City that killed 168 people, it did not go unnoticed that the perpetrators of the attack, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols (and a third accomplice), met and served together in the Army. Oklahoma City remains the deadliest domestic terrorism attack in U.S. history.

That same year, white, active-duty soldiers murdered two Black people in North Carolina, who they picked randomly due to their race. The white supremacist views of one of the murderers was apparently ‘well-known’ prior to the murders, according to a Washington Post article, underscoring why identifying and reporting extremist activity before there is violence is so important. The then-secretary of the Army launched a task force on racial extremism.”

Sent Saturdays